This article describes the ancient Persian education system, its importance and learning methods by students.

There is very little information with regard to the training of children during the Achaemenid period. In the two Elamite documents written by Persepolis in the 23rd regal year of Darius the Great in and around 499 B.C.E. whereby it was mentioned “Persian boys (who) are copying texts” finds a reference.

Education in Ancient Persia

These texts in question were from the records of the issue of grain to twenty-nine individuals and wine to sixteen. It could have been possible that the boys were learning Persian cuneiform script, which was probably known only to a few scribes, as it was used mainly for royal triumphal inscriptions.

Most of the nobles and highly placed Persian civil servants were literate, and writing played part in standard Persian education. The Persians also used foreign scribes particularly for writing chiefly in Aramaic in the state chancery.

Some Idea of Typical Persian Education

However, there have been several Greek sources which provide some idea of typical Persian education. According to Herodotus, Persian boys were not allowed into the presence of their fathers until the age of five years; until then they lived among the women. From ages five to twenty years they were trained in horsemanship, swordsmanship, archery, and telling the truth.

Ancient Persians regarded lying as the worst of offenses, whereas prowess in arms was the mark of manliness. Xenophon wrote in Cyropaedia that until the age of sixteen or seventeen years the sons of Persian nobles were brought up at the royal court, practicing riding, archery, throwing the spear, and hunting.

They were also instructed injustice, obedience, endurance, and self-restraint. Thus, it was evident that apart from ethical guidance, the focus as also on Persian education was to produce efficient soldiers. This conclusion is confirmed by the tomb inscription of Darius the Great:

Training in Ancient Persia

“Trained am I both with hands and with feet. As a horseman, I am a good horseman. As a bowman, I am a good bowman both afoot and on horseback. As a spearman, I am a good spearman both afoot and on horseback”

In Alcibiades it is noted that Persian princes were assigned at the age of fourteen years to four eminent Persians, called respectively the “wisest,” “most just,” “most temperate,” and “bravest,” who tutored them in the worship of the gods, government, temperance, and courage respectively. Plutarch mentioned a priest who taught “the wisdom of the Magi” to Cyrus the Younger.

There is practically no information on education in the eastern satrapies of the Achaemenid Empire. However, the evidence for Babylonia and Egypt, where traditional educational systems continued under Persian rule, was somewhat extensive. In both provinces, formal education was restricted to boys.

Reading and writing, as well as some grammar, mathematics, and astronomy, were taught in scribal schools. In Achaemenid Babylonia literacy also was widespread among the non-Iranian population; scribes were numerous and included the sons of shepherds, fishermen, weavers, and the like. Many school texts have survived from Mesopotamia.

Ancient Persia Education Related Facts

These included the Sumerian-Babylonian dictionaries, tablets with cuneiform signs, and collections of examples of grammatical usage and exercises. The literacy rate was even higher among the Achaemenid military colonists in Elephantine in Egypt, where witnesses to contracts in Aramaic usually signed their own names.

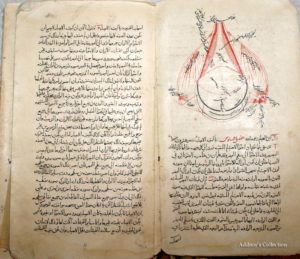

Darius, I ordered the restoration of the medical school at Sais in Egypt. It seems, however, that among the Egyptians education remained the privilege of the nobility: The Egyptian dignitary Ujahorresne declared that there were no children of “nobodies” among the students in this medical school.

Thus the importance of knowledge and education among ancient Persians can be observed even in their early childhood education. This attention to education and more particularly towards medical education was, in fact, a crucial feature of Persian culture and its dynamic civilization.